Below please find a small educational video explaining the general concepts on dark matter and how astrophysicists are able to detect it without seeing it!

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

Blog #38, Extra Credit Video Project, Dark Matter

Below please find a small educational video explaining the general concepts on dark matter and how astrophysicists are able to detect it without seeing it!

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Blog #36, Worksheet #12.1, Problem #1 and 2(d), Dark Matter Halos

1. Linear perturbation theory. In this and the next exercise we study how small fluctuations in the initial condition of the universe evolve with time, using some basic fluid dynamics. In the early universe, the matter/radiation distribution of the universe is very homogeneous and isotropic. At any given time, let us denote the average density of the universe as p(t). Nonetheless, there are some tiny fluctuations and not everywhere exactly the same. So let us define the density at co-moving position r and time t as ρ(x,t) and the relative density contrast.

In this exercise we focus on the linear theory, namely, the density contrast in the problem remains small enough so we only need consider terms linear in δ. We assume that cold dark matter, which behaves like dust (that is, it is pressureless) dominates the content of the universe at the early epoch. The absence of pressure simplifies the fluid dynamics equations used to characterize the problem.

a) In the linear theory, it turns out that the fluid equations simplify such that the density contrast δ satisfies the following second-order differential equation.

where a(t) is the scale factor of the universe. Notice that remarkably in the linear theory this equation does not contain spatial derivatives. Show that this means that the spatial shape of the density fluctuations is frozen in comoving coordinates, only their amplitude changes. Namely this means that we can factorize

Derive this differential equation.

We begin with the equation \[\ddot{\delta} + \frac{2 \dot{a}}{a} \dot{\delta} = 4 \pi G \bar{\rho} \delta\]We then use the relationship that \[\delta = D \tilde{\delta}\]We then plug in and simplify our equation to get a quadratic with variable D. \[\ddot{D} + \frac{2 \dot{a}}{a} \dot{D} - 4 \pi G \bar{\rho} D = 0 \]

b) Now let us consider a matter dominated flat universe, so that ρ(t) = a^-3ρ(c,0) where ρ(c,0) is the critical density today, 3H^2/8πG as in Worksheet 11.1 (aside: such a universe sometimes is called the Einstein-de Sitter model). Recall that the behaviour of the scale factor of this universe can be written a(t) = (3Ht/2)^2/3 , which you learned in previous worksheets, and solve the differential equation for D(t). Hint: you can use the ansatz D(t) is prop to t^q and plug it into the equation that you derived above; and you will end up with a quadratic equation for q. There are two solutions for q, and the general solution for D is a linear combination of two components: One gives you a growing function in t, denoting it as D(t); another decreasing function in t, denoting it as D(t).

We are then given that \[\bar{\rho} = a^{-3} {\rho}_{c,o}\]Where \[a = (\frac{3 H_0 t}{2})^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad {\rho}_{c,o} = \frac{3 H_0}{8 \pi G}\]We combine these to show \[\bar{\rho} = \frac{1}{6 \pi G t^2}\]We are then asked to approximate \(D\) as \(t^q

\). Plugging this into our quadratic, along with \(\bar{\rho}\), \(a\) and \(\dot{a}\) we get \[0 = (q)(q-1)t^{q-2} + \frac{4q}{3}t^{q-2} - \frac{2}{3}t^{q-2}\]We divide by \(t^{q-2}\) and simplify to get \[q^2 + \frac{1}{3}q - \frac{2}{3} = 0\]Then we solve for q to get \[q = \frac{2}{3}, -1\] Which is the desired positive side and negative side solution that we expected. To solve for a final D, we put our two answers into a linear combination to give us \[D = t^{-1} + t^{\frac{2}{3}}\]where \[D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad D_- = t^{-1}\]

c) Explain why the D component is generically the dominant one in structure formation, and show that in the Einstein-de Sitter model, D(t) prop to a(t).

We can see of the bat that our \(D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) is proportion to \(a(t) = (\frac{3 H_0 t}{2})^{\frac{2}{3}}\) and the two will increase proportionally. We can also see that \(D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) will increase much faster than \(D_- = \frac{1}{t}\) and thus will dominate the overall D formula.

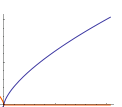

2d) Plot r as a function of t for all three cases (i.e. use y-axis for r and x-axis for t), and show that in the closed case, the particle turns around and collapse; in the open case, the particle keeps expanding with some asymptotically positive velocity; and in the flat case, the particle reaches an infinite radius but with a velocity that approaches zero.

In the first plot we can see the closed case, where the particle turns and collapses back to an incredibly small radius.

Eventually this graph will hit an asymptotically high velocity in which the particle is increasing radius at nearly an infinite rate. This is the case when the universe is modeled in an open system.

Finally for the flat case we can see that the radius is ever expanding but at a decreasing rate that will eventually flatten to a zero velocity.

#37, Free Form Post, Illustris Write Up

Illustris

The Illustris simulation is a massive computer program simulating the entire universe in its galaxies, black holes, gas dispersion, and even dark matter. The entire simulation has been compiled onto www.illustris-project.org and includes various images and videos that run through the hypothetical formation of the universe through various mediums.

We began our exploration by examining a 15 Mpc/h deep slice of the simulation. Shown below is the filter displaying the density of dark matter in the simulated universe. The lighter the shade of purple, the more densely packed the dark matter is.

We then selected a small portion of the simulation and ran a "halo query" to find the characteristics of a group of galaxies and their surrounding dark matter. The query returns the galaxy ID, position, stellar mass, halo mass, color, and magnitude for around 20 different galaxies in the selected 400 kpc/h portion.

We then created a histogram based on the halo mass and stellar mass of the selected galaxies.

From this plot we can see that while the stellar masses are relatively well distributed, the halo masses far favor the low mass halos. We can also determine the average amount of the halo mass that is made up of the stellar mass. Taking each percentage of (stellar mass/halo mass) and taking the average we can see that on average about 80% of the halo mass is made up of the stellar mass.

Exploring structure and Reionization

We then used various filters on the simulation to explore the differences between the stellar, gas, and dark matter densities of the structure. We looked at the gas and dark matter densities on large and small scales to find that while very similar on large and small scales, the dark matter is far more structured a large scale and the gas has much more form at very small scales (galactic scale). Still overall the gas has more form but less structure than the dark matter density over all. The stellar density is far less than both the gas and dark matter, but is incredibly well formed.

From the simulation we can see that the dark matter is far more structured than the universal gas density. This is because dark matter does not hold pressure and remains at very low temperature compared to its gas counterpart that gets very hot. The heat in the gas causes repelling forces that counter the gravitational forces that are trying to create the form of the universe. The dark matter remains cold and is almost solely worked on by the gravitational forces which can nicely form the dark matter into the filament like structure.

From the simulation we can also see some characteristics about the gas and dark matter distributions. For example, the densest parts of the gas are found towards the nuclei of medium to large galaxies as compared to the disk which moves outward at a less dense gradient. We can also see that most of the large galaxies accumulate in the clusters at filament centers rather than in open space. This is likely because the large masses of these galaxies create stronger gravitational pulls and bring together other large galaxies into major galactic clusters.

We were then asked to explore a video of the formation of the simulation. The video can be seen below:

The video shows the side by side development of the dark matter and gas of the simulated universe. We learned in previous worksheets that the developing gas was mostly hydrogen that absorbed much of the light before it was ionized and broken apart. The right simulation shows the slow development of gas over time as hydrogen absorbed most of the energy but did not ionize for a long period of time.

We can immediately see that dark matter dominated the development of the universe, forming much more complex structures before the gas even begins to form. You can see the filament structures of the dark matter forming far before the gas follows a similar formation pattern.

At a redshift of around 7.5 (or 0.7 billion years after the big bang) we begin to see the formation of the first ionized gasses. This is the end of the dark era mentioned above and brought forth the "epoch of reionization, as hydrogen molecules began to spread and make more complex structures.

During the redshift 2->0.5 we see the fastest development of galaxies and stellar mass. moving quickly from around 12->60 billion solar masses in the universe. During this time we see larger gas and dark matter structures breaking down into smaller ones, pulling nearby elements toward them to form larger structures and then continuously breaking down again. This hierarchal structure likely stems from the a central explosion (the big bang) starting the chain of events that created the rest of the structure for the universe over time. The gravity of the universe pulls objects closer together until their forces overwhelm and they must break apart to form new structures.

As mentioned before over a long time, the gravitational forces overcome their weaker intermolecular forces and pull the gas and dark matter of the structure into a filament form. However there is still interaction between the clusters and thus the clusters cannot form perfect spheres as we saw in the worksheet with halo collapse. There are too many forces present for the clusters to remain perfectly spherical and instead interact in such a way that they form longer, spindle like structures throughout the universe.

Saturday, November 28, 2015

Blog #35, Worksheet #11.1, Problem #3, Baryons and Photons

3. a) Despite the fact that the CMB has a very low temperature (that you have calculated above), the number of photon is enormous. Let us estimate what that number is. Each photon has energy hν. From equation (1), figure out the number density, nν, of the photon per frequency interval dν. Integrate over dν to get an expression for total number density of photon given temperature T. Now you need to keep all factors, and use the fact that

We start with the given equation 1) of \[\frac{8 \pi}{c^3} \cdot \frac{v^2}{e^{\frac{hv}{kT}} - 1} dv = n_v dv\]To integrate dv, we will use a u substitution and call \[u = \frac{hv}{kT}\] Which gives us \[du = \frac{h}{kT}dv \qquad and \qquad v^2 = \frac{k^2 T^2 u^2}{h^2}\] Plugging these relationships into our original equation 1) we are left with \[\frac{8 \pi k^3 T^3}{c^3 h^3} \cdot \frac{u^2}{e^u - 1} du = n_v dv \]We then integrate the left side from 0 to \(\infty\) and using the relationship that \[\int^{\infty}_0 \frac{x^2}{e^x - 1} dx \thickapprox 2.4 \]We end up with \[n_v dv = \frac{19.2 \pi k^3 T^3}{c^3 h^3}\]

b) (b) Use the following values for the constants: kB = 1.38x10^-16 erg K^-1 , c = 3.00x10^10cm s^-1 , h = 6.62x10^27 erg s, and use the temperature of CMB today that you have computed from 2d), to calculate the number density of photon today in our universe today (i.e. how many photons per cubic centimeter?)

For this part, we simply use our relationship from part a to solve for the number density of photons in our universe today. We solve \[\frac{19.2 \pi (1.38x10^{-16})^{3} (2.7)^{3}}{(3x10^10)^3 (6.62x10^{-27})^3} \thickapprox 400 \frac{photon}{cm^3}\]

c) Let us calculate the average baryon number density today. In general, baryons refer to protons or neutrons. The present-day density (matter + radiation + dark energy) of our Universe is 9.2x10^30g cm^3 . The baryon density is about 4% of it. The masses of proton and neutron are very similar (1.7x 10^24g). What is the number density of baryons?

We are told that the total density of the universe is equal to \[\rho_{total} = 9.2x10^{-30} \frac{g}{cm^3}\]and we are told that baryons make up 4% of the total density meaning \[\rho_{baryon} = 3.68x10^{-31} \frac{g}{cm^3} \]We also know that the average baryon weighs \(1.7x10^{-24} g \) so the number density of baryons is \[n_{baryon} = \frac{\rho_{baryon}}{1.7x10^{-24} g } = 2.16x10^{-7} \frac{baryon}{cm^3}\]

d) Divide the above two numbers, you get the baryon-to-photon ratio. As you can see, our universe contains much more photons than baryons (proton and neutron).

Finally, we compare the amount of baryons to photons and get \[\frac{400 \frac{photons}{cm^3}}{2.16x10^{-7} \frac{baryons}{cm^3}} \thickapprox 2x10^9 \frac {photon}{baryon}\] Showing that there are far far more photons in our universe than there are baryons, or there is a lot more light than matter!

Blog #34, Worksheet #11.1, Problem #4, Flatness Problem of The Big Bang Model

4. The flatness problem of the big bang model. Despite the success of the Big Bang model mentioned in the lecture, there are also problems with it. These problems mostly have to do with the initial conditions for the Big Bang model, and provide the motivations for scientists to seek deeper answers for the origin of the Big Bang. In this exercise we study one of those problems.

a) Recall the Friedman equation we learned in a previous lecture \[H^2 = \frac{8 \pi G \rho}{3} - \frac{k c^2}{a^2}\]. Rewrite this in terms of the density parameter \(\Omega\).

We began with the given equation \[H^2 = \frac{8 \pi G \rho}{3} - \frac{k c^2}{a^2}\]Solving this for \(\rho\) we get \[\rho = \frac{3 H^2}{8 \pi G} + \frac{3 k c^2}{8 a^2 \pi G}\]However we were told that when we assume that k = 0, we get our critical \(\rho\) which is \[\rho_c = \frac{3H^2}{8 \pi G}\]We substitute in our critical rho to get \[\rho = \rho_c + \frac{k c^2}{a^2 H^2} \rho_c \] We then solve for the desired \(\Omega\) ratio of \(\frac{\rho}{\rho_c}\) and get \[\Omega = 1 + \frac{k c^2}{a^2 H^2}\]as expected.

b) Consider the epoch of our universe that is dominated by matter. We have already computed the time-dependence of a and H in such a universe (refer to Worksheet 9.1). Use this result and a) to show the time-dependence of Ω.

To show the time dependence we have to relate our \(\Omega\) ratio to the time dependence of a. Getting rid of the constants in the equation above, we know \[\Omega \propto (a \cdot H)^{-2} \qquad and \qquad H = \frac{\dot{a}}{a}\] meaning \[\Omega \propto {\dot{a}}^{-2}\] From a previous worksheet we found that \[a \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad \dot{a} \propto t^{- \frac{1}{3}}\]Thus we have \[\Omega \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \]

c) Today, experiments have measured the density parameter of our universe is within 0.005 : Ω - 1 : 0.005, namely Ω is close to 1 today. Use your above result to determine the range of Ω - 1 at the time of CMB formation, using the fact that today the age of universe is about 13.7 billion years and the age of universe when the CMB formed was about 380, 000 years. From this exercise we see that in the early universe, the density parameter was very close to one. This is one of the issues of the Big Bang model – why is this special initial condition chosen? We provide one possible solution to this question in the next exercise.

Beginning with the equation we just solved for \[\Omega - 1 = \frac{kc^2}{a^2 H^2}\]and plugging in the time dependence we just found we are left with \[\Omega - 1 = C_0 t^{\frac{2}{3}}\]We then use the given information for \(\Omega -1\) and t to solve for \(C_0\). We solve that the time constant for light in this model is \[C_0 \thickapprox 8.73 x10^{-10} \]We then use this constant and the given time when the CMB was taken t = 380,000 to solve for the approximate density constant. \[\Omega - 1 = (8.73 x 10^{-10})(380,000)^{- \frac{2}{3}} = \pm 5 x 10^{-6} \]Because this answer is approximately zero, we can approximate that the density constant, \(\Omega\) at that time fits the estimation that \[\Omega \thickapprox 1 \]

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Blog #33, Free-Form Post, The Blue Marble and Spaceship Earth

After a tragedy like the horrors experienced this past weekend in Paris, it is hard to step back and see humanity as one united, whole species. With a world filled with so much hate and animosity, how could we all possibly be united under some joining force of humanity?

This weekend I was fortunate enough to attend the annual Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS) conference at Boston University. At the conference, multiple speakers spoke of the future of space travel, living on mars, and a variety of amazing space technologies. But one speaker, Frank White, a storied author and Professor at the Extension School, spoke about his expertise, The Overview Effect. Frank has been working with astronauts for the past 30 years to document and detail the experience of traveling to space and how it changes the psyche.

Known colloquially as the Overview Effect, Professor White describes a cognitive shift in awareness in astronauts who have been beyond the boundaries of Earth and seen our planet from a far, simply a vessel carrying 7 billion people through the vast emptiness of space. This realization that humans are so small, so insignificant in the grand scheme of things, is said to bring on an immense truth and actually some sadness in astronauts. A sadness over the fact that not everyone on the planet has the opportunity to experience the truth and still quarrels over things like borders, religion, and ideology instead of coming together under the ties of humanity.

Luckily, also at this conference were several companies extending the offer to bring everyday humans into low orbit, to look back onto our planet and discover what it is like to escape from the grips of Earth's problems. I hope that one day every human, who chooses to, has the ability to go to space and learn what countless astronauts have felt when looking back on the small blue marble, sitting on the forever expanses of black space.

image:

http://eoimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/imagerecords/55000/55418/AS17-148-22727_lrg.jpg

This weekend I was fortunate enough to attend the annual Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS) conference at Boston University. At the conference, multiple speakers spoke of the future of space travel, living on mars, and a variety of amazing space technologies. But one speaker, Frank White, a storied author and Professor at the Extension School, spoke about his expertise, The Overview Effect. Frank has been working with astronauts for the past 30 years to document and detail the experience of traveling to space and how it changes the psyche.

Known colloquially as the Overview Effect, Professor White describes a cognitive shift in awareness in astronauts who have been beyond the boundaries of Earth and seen our planet from a far, simply a vessel carrying 7 billion people through the vast emptiness of space. This realization that humans are so small, so insignificant in the grand scheme of things, is said to bring on an immense truth and actually some sadness in astronauts. A sadness over the fact that not everyone on the planet has the opportunity to experience the truth and still quarrels over things like borders, religion, and ideology instead of coming together under the ties of humanity.

Luckily, also at this conference were several companies extending the offer to bring everyday humans into low orbit, to look back onto our planet and discover what it is like to escape from the grips of Earth's problems. I hope that one day every human, who chooses to, has the ability to go to space and learn what countless astronauts have felt when looking back on the small blue marble, sitting on the forever expanses of black space.

image:

http://eoimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/imagerecords/55000/55418/AS17-148-22727_lrg.jpg

Blog #32, Worksheet #10.1, Problem #3, Observable Universe

3. Observable Universe. It is important to realize that in our Big Bang universe, at any given time,

the size of the observable universe is finite. The limit of this observable part of the universe is called

the horizon (or particle horizon to be precise, since there are other definitions of horizon.) In this

problem, we’ll compute the horizon size in a matter dominated universe in co-moving coordinates.

To compute the size of the horizon, let us compute how far the light can travel since the Big Bang.

(a) First of all - Why do we use the light to figure out the horizon size?

Well we classify the horizon as the edge of the observable universe and we can only observe as far as light has traveled. Thus if we want to calculate the size of the "observable" universe, we must use the fastest known observable element, which in our case is light.

(b) Light satisfies the statement that \(ds^2 = 0\). Using the FRW metric, write down the differential equation that describes the path light takes. We call this path the geodesic for a photon. Choosing convenient coordinates in which the light travels in the radial direction so that we can set dθ = dφ = 0, find the differential equation in terms of the coordinates t and r only.

We begin with the general FRW metric given earlier in the worksheet and set ds^2 = 0 giving us \[c^2 dt^2 = a^2 (t) [\frac{dr^2}{1-kr^2} + r^2 (d \theta^2 + sin^2 \theta d \phi^2)] \]We simplify given the information that dθ = dφ = 0 and get \[c^2 dt^2 = \frac{a^2 (t) dr^2}{1-kr^2}\]which gives us an equation \[c^2 = \frac{a^2}{1-kr^2} (\frac{dr}{dt})^2\]

(c) Suppose we consider a flat universe. Let’s consider a matter dominated universe so that a(t) as a function of time is known (in the last worksheet). Find the radius of the horizon today (at t = t0). (Hint: move all terms with variable r to the LHS and t to the RHS. Integrate both sides, namely r from 0 to rhorizon and t from 0 to t0.)

We begin with the equation we just derived and put in the fact that for a flat universe, k = 0. Thus we are left with \[c^2 = a^2 (\frac{dr}{dt})^2 \rightarrow dr = \frac{c}{a(t)} dt \] In last week's worksheet we found that a(t) in modern times is proportional to \(t^{\frac{2}{3}}\). We then plug into our equation \[a(t) = a_0 (\frac{t}{t_0})^{2/3}\] \[dr = \frac{c t_0^{\frac{2}{3}}}{a_0 t^{\frac{2}{3}}}\]We then integrate both sides and get \[R = \frac{c}{a_0} t_0^{\frac{2}{3}} \int_{0}^{t_0} t^{- \frac{2}{3}} = \frac{c}{a_0} t_0^{\frac{2}{3}} \cdot 3 t_0^{\frac{1}{3}}\]Which gives us our final relationship of \[R = \frac{3c t_0}{a_0}\]

(a) First of all - Why do we use the light to figure out the horizon size?

Well we classify the horizon as the edge of the observable universe and we can only observe as far as light has traveled. Thus if we want to calculate the size of the "observable" universe, we must use the fastest known observable element, which in our case is light.

(b) Light satisfies the statement that \(ds^2 = 0\). Using the FRW metric, write down the differential equation that describes the path light takes. We call this path the geodesic for a photon. Choosing convenient coordinates in which the light travels in the radial direction so that we can set dθ = dφ = 0, find the differential equation in terms of the coordinates t and r only.

We begin with the general FRW metric given earlier in the worksheet and set ds^2 = 0 giving us \[c^2 dt^2 = a^2 (t) [\frac{dr^2}{1-kr^2} + r^2 (d \theta^2 + sin^2 \theta d \phi^2)] \]We simplify given the information that dθ = dφ = 0 and get \[c^2 dt^2 = \frac{a^2 (t) dr^2}{1-kr^2}\]which gives us an equation \[c^2 = \frac{a^2}{1-kr^2} (\frac{dr}{dt})^2\]

(c) Suppose we consider a flat universe. Let’s consider a matter dominated universe so that a(t) as a function of time is known (in the last worksheet). Find the radius of the horizon today (at t = t0). (Hint: move all terms with variable r to the LHS and t to the RHS. Integrate both sides, namely r from 0 to rhorizon and t from 0 to t0.)

We begin with the equation we just derived and put in the fact that for a flat universe, k = 0. Thus we are left with \[c^2 = a^2 (\frac{dr}{dt})^2 \rightarrow dr = \frac{c}{a(t)} dt \] In last week's worksheet we found that a(t) in modern times is proportional to \(t^{\frac{2}{3}}\). We then plug into our equation \[a(t) = a_0 (\frac{t}{t_0})^{2/3}\] \[dr = \frac{c t_0^{\frac{2}{3}}}{a_0 t^{\frac{2}{3}}}\]We then integrate both sides and get \[R = \frac{c}{a_0} t_0^{\frac{2}{3}} \int_{0}^{t_0} t^{- \frac{2}{3}} = \frac{c}{a_0} t_0^{\frac{2}{3}} \cdot 3 t_0^{\frac{1}{3}}\]Which gives us our final relationship of \[R = \frac{3c t_0}{a_0}\]

Blog #31, Worksheet #10.1, Problem #2, Circumference Ratios

2) . Ratio of circumference to radius. Let’s continue to study the difference between closed, flat

and open geometries by computing the ratio between the circumference and radius of a circle.

(a) To compute the radius and circumference of a circle, we look at the spatial part of the metric and concentrate on the two-dimensional part by setting dφ = 0 because a circle encloses a two-dimensional surface. For the flat case, this part is just \[{ds_{2D}}^2 = d r^2 + r^2 d \theta^2\] The circumference is found by fixing the radial coordinate (r = R and dr = 0) and both sides of the equation (note that θ is integrated from 0 to 2π).

The radius is found by fixing the angular coordinate (θ, dθ = 0) and integrating both sides (note that dr is integrated from 0 to R).

Compute the circumference and radius to reproduce the famous Euclidean ratio 2π.

We first set r = R and dr = 0 to find the circumference. We get \[ds^2 = R^2 d \theta^2 \]We then take the root of both sides to get \[ds = R d \theta\]and when we integrate both sides we get \[\int_{0}^{s} ds = \int_{0}^{2 \pi} R d \theta\]Which gives us \[S_{circ} = 2 \pi R\]Then we solve for the radius by setting \(d \theta = 0 \) and get \[S_{rad} = \int_{0}^{R} dr = R \]Finally we take the ratio of our S factors to get the desired ratio \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi R}{R} = 2 \pi \]

(b) For a closed geometry, we calculated the analogous two-dimensional part of the metric in Problem (1). This can be written as: \[{ds_{2D}}^2 = d \xi^2 + sin \xi^2 d \theta^2\] Repeat the same calculation above and derive the ratio for the closed geometry. Compare your results to the flat (Euclidean) case; which ratio is larger? (You can try some arbitrary values of ξ to get some examples.)

We repeat a similar process compared to part a) although now our \(S_{circ}\) comes out to be \[S = \int_{0}^{2 \pi} sin X d \theta = 2 \pi sin X\]As in part a), our radius integral simply comes out to \[S_{rad} = X\]Then we place the same ratio as in part a) to get \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi sin X}{X}\]We know that the function \(\frac{sin(X)}{X}\) can never be greater than one (see plot below). Thus the flat ratio will always be larger than the closed case, except at X = 0.

(c) Repeat the same analyses for the open geometry, and comparing to the flat case.

The open case is identical to the to the closed case except where the closed case has a sin term, the open case has a sinh term. This is due to the \(\frac{dr^2}{1- kr^2}\) that reduces to sinusoidal terms for the closed case, yet remains in the open system. Thus our ratio for the the open case becomes \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi sinh X}{X}\]However the plot of \(\frac{sinh(X)}{X}\) is always rising and must always be larger than the flat case of \(2 \pi\) (see graph below).

(d) You may have noticed that, except for the flat case, this ratio is not a constant value. However, in both the open and closed case, there is a limit where the ratio approaches the flat case. Which limit is that?

As the above graphs show, the only time that both cases approach the flat ratio of \(2 \pi\) is time 0. When we estimate the universe as taking different spacetime geometries, we still approximate all estimates as flat because the universe is so large and crosses such a expansive time, that any approximations we make are based on a very small, short time period and can be approximated as 0.

(a) To compute the radius and circumference of a circle, we look at the spatial part of the metric and concentrate on the two-dimensional part by setting dφ = 0 because a circle encloses a two-dimensional surface. For the flat case, this part is just \[{ds_{2D}}^2 = d r^2 + r^2 d \theta^2\] The circumference is found by fixing the radial coordinate (r = R and dr = 0) and both sides of the equation (note that θ is integrated from 0 to 2π).

The radius is found by fixing the angular coordinate (θ, dθ = 0) and integrating both sides (note that dr is integrated from 0 to R).

Compute the circumference and radius to reproduce the famous Euclidean ratio 2π.

We first set r = R and dr = 0 to find the circumference. We get \[ds^2 = R^2 d \theta^2 \]We then take the root of both sides to get \[ds = R d \theta\]and when we integrate both sides we get \[\int_{0}^{s} ds = \int_{0}^{2 \pi} R d \theta\]Which gives us \[S_{circ} = 2 \pi R\]Then we solve for the radius by setting \(d \theta = 0 \) and get \[S_{rad} = \int_{0}^{R} dr = R \]Finally we take the ratio of our S factors to get the desired ratio \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi R}{R} = 2 \pi \]

(b) For a closed geometry, we calculated the analogous two-dimensional part of the metric in Problem (1). This can be written as: \[{ds_{2D}}^2 = d \xi^2 + sin \xi^2 d \theta^2\] Repeat the same calculation above and derive the ratio for the closed geometry. Compare your results to the flat (Euclidean) case; which ratio is larger? (You can try some arbitrary values of ξ to get some examples.)

We repeat a similar process compared to part a) although now our \(S_{circ}\) comes out to be \[S = \int_{0}^{2 \pi} sin X d \theta = 2 \pi sin X\]As in part a), our radius integral simply comes out to \[S_{rad} = X\]Then we place the same ratio as in part a) to get \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi sin X}{X}\]We know that the function \(\frac{sin(X)}{X}\) can never be greater than one (see plot below). Thus the flat ratio will always be larger than the closed case, except at X = 0.

(c) Repeat the same analyses for the open geometry, and comparing to the flat case.

The open case is identical to the to the closed case except where the closed case has a sin term, the open case has a sinh term. This is due to the \(\frac{dr^2}{1- kr^2}\) that reduces to sinusoidal terms for the closed case, yet remains in the open system. Thus our ratio for the the open case becomes \[\frac{S_{circ}}{S_{rad}} = \frac{2 \pi sinh X}{X}\]However the plot of \(\frac{sinh(X)}{X}\) is always rising and must always be larger than the flat case of \(2 \pi\) (see graph below).

(d) You may have noticed that, except for the flat case, this ratio is not a constant value. However, in both the open and closed case, there is a limit where the ratio approaches the flat case. Which limit is that?

As the above graphs show, the only time that both cases approach the flat ratio of \(2 \pi\) is time 0. When we estimate the universe as taking different spacetime geometries, we still approximate all estimates as flat because the universe is so large and crosses such a expansive time, that any approximations we make are based on a very small, short time period and can be approximated as 0.

Sunday, November 8, 2015

Blog #30, Lab 2 Preview

In the second lab we will be using the millimeter-wave telescope at the Harvard College Observatory

to observe giant molecular clouds (GMCs) spread throughout the inner regions of the Milky Way. We will be pointing the telescope at a variety of GMCs to try and calculate orbital velocities in an attempt to us the data for a variety of calculations including finding redshifts of the clouds, number of stars interior to the sun, galactic age of the sun, and plot a rough orbit of the galaxy.

- What is going to be the typical integration time per point?

Amazingly, the millimeter telescope only needs an integration time of 2-3 minutes per point and can see up to 50,000 light years away in that time.

- Over what range of longitude do you plan to observe?

I plan to observe over galactic longitudes b ∼ 10° to ∼ 70°

- How many (l,b) positions do you plan to observe?

We plan to observe 4 different GMCs and their associated galactic (l,b) positions.

- Will all your target positions be above 30° when you plan to observe them?

We need all of our targets to be above 30° or we will get messy data from noise in the sky. Luckily we are observing around noon and all of our targets should be readily visible.

- At what LST are you going to start observing? At what EST?

- What is going to be the typical integration time per point?

Amazingly, the millimeter telescope only needs an integration time of 2-3 minutes per point and can see up to 50,000 light years away in that time.

- Over what range of longitude do you plan to observe?

I plan to observe over galactic longitudes b ∼ 10° to ∼ 70°

- How many (l,b) positions do you plan to observe?

We plan to observe 4 different GMCs and their associated galactic (l,b) positions.

- Will all your target positions be above 30° when you plan to observe them?

We need all of our targets to be above 30° or we will get messy data from noise in the sky. Luckily we are observing around noon and all of our targets should be readily visible.

We will be observing around noon EST, which ends up being around 15:30 LST.

Blog #29, Worksheet #9.1, Question 2, GR modifications to Friedmann Equations

2. In Question 1, you have derived the Friedmann Equation in a matter-only universe in the New- tonian approach. That is, you now have an equation that describes the rate of change of the size of the universe, should the universe be made of matter (this includes stars, gas, and dark matter) and nothing else. Of course, the universe is not quite so simple. In this question we’ll introduce the full Friedmann equation which describes a universe that contains matter, radiation and/or dark energy. We will also see some correction terms to the Newtonian derivation.

(a) The full Friedmann equations follow from Einstein’s GR, which we will not go through in this course. Analogous to the equations that we derived in Question 1, the full Friedmann equations express the expansion/contraction rate of the scale factor of the universe in terms of the properties of the content in the universe, such as the density, pressure and cosmological constant. We will directly quote the equations below and study some important consequences.

Starting from these two equations, derive the third Friedmann equation, which governs the way average density in the universe changes with time.

The result you got has the following simple interpretation. The cold matter behaves like “cosmological dust” and it is pressureless (not to be confused with warm/hot dust in the interstellar medium!). As the universe expands, the mass of each dust particle is fixed, but the number density of the dust is diluted - inversely proportional to the volume.

Using the relation between (\rho\) and a that you just derived and the first Friedmann equation, derive the differential equation for the scale factor a for the matter dominated universe.

c) Let us repeat the above exercise for a universe filled with radiation only. For radiation, \(P = \frac{1}{3} \rho c^2 \) and Λ = 0. Again, use the third Friedmann equation to see how the density of the radiation changes as a function of scale factor.

d) Imagine a universe dominated by the cosmological-constant-like term. Namely in the Friedmann equation, we can set ρ = 0 and P = 0 and only keep Λ nonzero.

Simply put, if we look at our answers for b) and c) we see that \[a_{matter} \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad a_{radiation} \propto t^{\frac{1}{2}}\]Thus we can say that the portion of the universe dominated by matter will expand much faster than that of radiation so over a long period of time, the matter will become dominant because it is constantly expanding faster.

(f) Suppose the energy density of a universe is dominated by similar amount of matter and dark energy. (This is the case for our universe today. Today our universe is roughly 68% in dark energy and 32% in matter, including 28% dark matter and 5% usual matter, which is why it is acceleratedly expanding today.) As the universe keeps expanding, which content, matter or the dark energy, will become the dominant component? Why? What is the fate of our universe?

In a similar manner \[a_{matter} \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad a_{energy} \propto e^t\] \(e^t\) expands much much faster than \(t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) so our universe will soon be far dominated by dark matter. We have a very dark future to look forward to.

(a) The full Friedmann equations follow from Einstein’s GR, which we will not go through in this course. Analogous to the equations that we derived in Question 1, the full Friedmann equations express the expansion/contraction rate of the scale factor of the universe in terms of the properties of the content in the universe, such as the density, pressure and cosmological constant. We will directly quote the equations below and study some important consequences.

Starting from these two equations, derive the third Friedmann equation, which governs the way average density in the universe changes with time.

As suggested in the assignment, much of the math has been shortened or skip due to tediousness but the processes will be described for each step. We begin by multiplying equation (1) on the sheet by a and taking the time derivative then plugging in equation 2 to cancel \(\ddot{a}\). We end up with \[\frac{4 \pi G a \dot{a}}{3c^2} (\rho c^2 + 3P) = \frac{8}{3} \pi a \dot{a} G \rho + \frac{4}{3} \pi a^2 G \dot{\rho}\]We then cancel and simplify both sides to get \[- \frac{3P \dot{a}}{c^2} = 3 \dot{a} \rho + a \dot{\rho}\]Finally we multiply both sides by \(c^2\) and divide by a to get our desired final answer of \[\dot{\rho} c^2 = -3 \frac{\dot{a}}{a} (\rho c^2 + P) \]

(b) Cold matter dominated universe. If the matter is cold, its pressure P = 0, and the cosmological constant Λ = 0. Use the third Friedmann equation to derive the evolution of the density of the matter \(\rho\) as a function of the scale factor of the universe a. You can leave this equation in terms of (\rho\) , (\rho\)0,a and a0, where (\rho\)0 and a0 are current values of the mass density and scale factor.

The result you got has the following simple interpretation. The cold matter behaves like “cosmological dust” and it is pressureless (not to be confused with warm/hot dust in the interstellar medium!). As the universe expands, the mass of each dust particle is fixed, but the number density of the dust is diluted - inversely proportional to the volume.

Using the relation between (\rho\) and a that you just derived and the first Friedmann equation, derive the differential equation for the scale factor a for the matter dominated universe.

We can derive from the third Friedmann equation that \[\frac{\dot{\rho}}{\rho} \propto \frac{\dot{a}}{a} \rightarrow \rho \propto a^{-3} \]We then solve the first Friedmann equation with \(\Lambda = 0\) and \(k = 0 \) giving us \[\dot{a}^2 = \frac{8 \pi}{3} G \rho a^2 \propto \frac{8 \pi}{3} G a^{-1} \]Which means \[\dot{a} \propto a^{- \frac{1}{2}} \propto \frac{da}{dt} \]We then separate and integrate both sides \[\int{a^{\frac{1}{2}} da} = \int{dt} \] \[a^{\frac{3}{2}} \propto t \rightarrow a \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}}\]

As explained in the assignment, parts b, c, and d are very similar in their mathematical process. We follow the same steps as in part b to show \[\rho \propto a^{-4}\]Which, using the same reasoning would give us \[\dot{a} \propto a^{-1} \propto \frac{da}{dt} \] and when we integrate we would get \[a^2 \propto t \rightarrow a \propto t^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

d) Imagine a universe dominated by the cosmological-constant-like term. Namely in the Friedmann equation, we can set ρ = 0 and P = 0 and only keep Λ nonzero.

To avoid repetition, we will skip the same steps seen in part b and c and give the answer as \[a(t) \propto e^t\]Meaning that in a dark energy dominated universe, the scale factor increases exponentially as time progresses.

(e) Suppose the energy density of a universe at its very early time is dominated by half matter

and half radiation. (This is in fact the case for our universe 13.7 billion years ago and only 60

thousand years after the Big Bang.) As the universe keeps expanding, which content, radiation

or matter, will become the dominant component? Why?

Simply put, if we look at our answers for b) and c) we see that \[a_{matter} \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad a_{radiation} \propto t^{\frac{1}{2}}\]Thus we can say that the portion of the universe dominated by matter will expand much faster than that of radiation so over a long period of time, the matter will become dominant because it is constantly expanding faster.

In a similar manner \[a_{matter} \propto t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad a_{energy} \propto e^t\] \(e^t\) expands much much faster than \(t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) so our universe will soon be far dominated by dark matter. We have a very dark future to look forward to.

Blog #28, Worksheet #9.1, Question 1, Matter-Only Universe

1) In this exercise, we will derive the first and second Friedmann equations of a homogeneous, isotropic and matter-only universe. We use the Newtonian approach. Consider a universe filled with matter which has a mass density \(\rho (t)\). Note that as the universe expands or contracts, the density of the matter changes with time, which is why it is a function of time t. Now consider a mass shell of radius R within this universe. The total mass of the matter enclosed by this shell is M. In the case we consider (homogeneous and isotropic universe), there is no shell crossing, so M is a constant.

(a) What is the acceleration of this shell? Express the acceleration as the time derivative of velocity, \(\dot{v}\) (pronounced v-dot) to avoid confusion with the scale factor a (which you learned about last week).

We start with the simple equation for force so that we can relate acceleration to constants in our system. We know that \[F = m \dot{v} = - \frac{GMm}{r^2}\] We then simply cancel m's and rearrange to solve \[\dot{v} = - \frac {GM}{r^2} \]

(b) To derive an energy equation, it is a common trick to multiply both sides of your acceleration equation by v. Turn your velocity, v, into dR/dt , cancel dt, and integrate both sides of your equation. This is an indefinite integral, so you will have a constant of integration; combine these integration constants call their sum C.

Once we multiply both sides by v and cancel dt, we are left with \[\dot{v} dr = - \frac{GM}{r^2} dr \] and when we integrate both sides we get \[\frac{\dot{r}^2}{2} = \frac{GM}{r} + C\]Then we rearrange to get our desired final answer of \[\frac{\dot{r}^2}{2} - \frac{GM}{r} = C \]

(c) Express the total mass M using the mass density, and plug it into the above equation. Rearrange your equation to give an expression for \((\frac{\dot{R}}{R})^2\) where \(\dot{R}\) is equal to dR/dt.

We know that \[\rho = \frac{M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3}\] which gives us \[M = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho\]We then plug in to our equation from part b) and get \[\frac{\dot{r}}{2} - \frac{4}{3} \pi G \rho r^2 = C \] Finally we multiply through by 2 and divide by \(R^2\) to get the desired left side of the equation. Our final answer comes out to \[(\frac{\dot{r}}{r})^2 = \frac{8}{3} \pi G \rho + \frac{2C}{r^2}\]

(d) R is the physical radius of the sphere. It is often convenient to express R as R = a(t)r, where r is the comoving radius of the sphere. The comoving coordinate for a fixed shell remains constant in time. The time dependence of R is captured by the scale factor a(t). The comoving radius equals to the physical radius at the epoch when a(t) = 1. Rewrite your equation in terms of the comoving radius, R, and the scale factor, a(t).

(f) Derive the first Friedmann Equation: From the previous worksheet, we know that \(H(t) = \frac{\dot{a}}{a} \). Plugging this relation into your above result and identifying the constant \(\frac{2C}{r^2} = -kc^2 \) where k is the “curvature” parameter, you will get the first Friedmann equation. The Friedmann equation tells us about how the shell of expands or contracts; in other words, it tells us about the Hubble expansion (or contracration) rate of the universe.

We know \[H(t) = \frac{\dot{a}}{a} \qquad and \qquad \frac{2C}{r^2} = -kc^2\]Plugging into our equation from part d) we get \[H(t) = \frac{8}{3} \pi G \rho - \frac{kc^2}{a^2}\]

(g) Derive the second Friedmann Equation: Now express the acceleration of the shell in terms of the density of the universe, and replace R with R = a(t)r. You should see that \(\frac{\ddot{a}}{a} = - \frac{4 \pi}{3} G \rho \) which is known as the second Friedmann equation.The more complete second Friedmann equation actually has another term involving the pressure following from Einstein’s general relativity (GR), which is not captured in the Newtonian derivation. If the matter is cold, its pressure is zero. Otherwise, if it is warm or hot, we will need to consider the effect of the pressure.

(a) What is the acceleration of this shell? Express the acceleration as the time derivative of velocity, \(\dot{v}\) (pronounced v-dot) to avoid confusion with the scale factor a (which you learned about last week).

We start with the simple equation for force so that we can relate acceleration to constants in our system. We know that \[F = m \dot{v} = - \frac{GMm}{r^2}\] We then simply cancel m's and rearrange to solve \[\dot{v} = - \frac {GM}{r^2} \]

(b) To derive an energy equation, it is a common trick to multiply both sides of your acceleration equation by v. Turn your velocity, v, into dR/dt , cancel dt, and integrate both sides of your equation. This is an indefinite integral, so you will have a constant of integration; combine these integration constants call their sum C.

Once we multiply both sides by v and cancel dt, we are left with \[\dot{v} dr = - \frac{GM}{r^2} dr \] and when we integrate both sides we get \[\frac{\dot{r}^2}{2} = \frac{GM}{r} + C\]Then we rearrange to get our desired final answer of \[\frac{\dot{r}^2}{2} - \frac{GM}{r} = C \]

(c) Express the total mass M using the mass density, and plug it into the above equation. Rearrange your equation to give an expression for \((\frac{\dot{R}}{R})^2\) where \(\dot{R}\) is equal to dR/dt.

We know that \[\rho = \frac{M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3}\] which gives us \[M = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho\]We then plug in to our equation from part b) and get \[\frac{\dot{r}}{2} - \frac{4}{3} \pi G \rho r^2 = C \] Finally we multiply through by 2 and divide by \(R^2\) to get the desired left side of the equation. Our final answer comes out to \[(\frac{\dot{r}}{r})^2 = \frac{8}{3} \pi G \rho + \frac{2C}{r^2}\]

(d) R is the physical radius of the sphere. It is often convenient to express R as R = a(t)r, where r is the comoving radius of the sphere. The comoving coordinate for a fixed shell remains constant in time. The time dependence of R is captured by the scale factor a(t). The comoving radius equals to the physical radius at the epoch when a(t) = 1. Rewrite your equation in terms of the comoving radius, R, and the scale factor, a(t).

(e) Rewrite the above expression so \((\frac{\dot{a}}{a})^2 appears alone on the left side of the equation.

This step only requires replacing the r's in part c) with a's to account for the comoving radius.

\[(\frac{\dot{a}}{a})^2 = \frac{8}{3} \pi G \rho + \frac{2C}{(a(t)r)^2}\]

We know \[H(t) = \frac{\dot{a}}{a} \qquad and \qquad \frac{2C}{r^2} = -kc^2\]Plugging into our equation from part d) we get \[H(t) = \frac{8}{3} \pi G \rho - \frac{kc^2}{a^2}\]

(g) Derive the second Friedmann Equation: Now express the acceleration of the shell in terms of the density of the universe, and replace R with R = a(t)r. You should see that \(\frac{\ddot{a}}{a} = - \frac{4 \pi}{3} G \rho \) which is known as the second Friedmann equation.The more complete second Friedmann equation actually has another term involving the pressure following from Einstein’s general relativity (GR), which is not captured in the Newtonian derivation. If the matter is cold, its pressure is zero. Otherwise, if it is warm or hot, we will need to consider the effect of the pressure.

We begin with \[\dot{v} = \ddot{r} = \ddot{a}(t) r = - \frac{GM}{r^2}\]Then we substitute as we did earlier for density, replacing r with a(t)r and get \[\frac{-4 \pi G \rho a(t)r}{3} = \ddot{a}(t)r\]Finally we cancel r's and divide by a to get a final answer of \[-\frac{4}{3} \pi G \rho = \frac{\ddot{a}}{a}\]

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Blog #27, Worksheet #8.1, Problem #3, Hubble Time

3. It is not strictly correct to associate this ubiquitous distance-dependent redshift we observe with the

velocity of the galaxies (at very large separations, Hubble’s Law gives ‘velocities’ that exceeds the

speed of light and becomes poorly defined). What we have measured is the cosmological redshift,

which is actually due to the overall expansion of the universe itself. This phenomenon is dubbed

the Hubble Flow, and it is due to space itself being stretched in an expanding universe.

Since everything seems to be getting away from us, you might be tempted to imagine we are located at the centre of this expansion. But, as you explored in the opening thought experiment, in actuality, everything is rushing away from everything else, everywhere in the universe, in the same way. So, an alien astronomer observing the motion of galaxies in its locality would arrive at the same conclusions we do.

In cosmology, the scale factor, \(a(t)\), is a dimensionless parameter that characterizes the size of the universe and the amount of space in between grid points in the universe at time t. In the current epoch, t = t0 and \(a(t_0) = 1\). \(a(t)\) is a function of time. It changes over time, and it was smaller in the past (since the universe is expanding). This means that two galaxies in the Hubble Flow separated by distance \(d_0 = d(t_0)\) in the present were \(d(t) = a(t)d_0\) apart at time t. The Hubble Constant is also a function of time, and is defined so as to characterize the fractional rate of change of the scale factor: \[H(t) = \frac{1}{a(t)} \frac{da}{dt}\]and the Hubble Law is locally valid for any t: \[v = H(t)d\]where v is the relative recessional velocity between two points and d the distance that separates them.

a) Assume the rate of expansion, \(\dot{a} = \frac{da}{dt}\), has been constant for all time. How long ago was the Big Bang (i.e. when a(t = 0) 0)? How does this compare with the age of the oldest globular clusters (~12 Gyr)? What you will calculate is known as the Hubble Time.

We want to solve for the time We are given that \(a_0\) is the base at which we characterize the size of the universe from the current epoch and assumes the number 1. We also know that \(H_0\) is a constant for the the current epoch found in question #2 of the worksheet. Using this information we can solve show that \[H_0 = \frac{\dot{a}}{a_0}\]Because we said that a = 1 at the current epoch we can say that \[H_0 = \dot{a} = \frac{da}{dt}\]We then get \[\int_{0}^{t_0} da = \int_{0}^{t_0} H_0 dt\]Which gives us \[a(t_0) = H_0 t_0\]We are looking to solve for \(t_0\) and once we rearrange we get \[t_0 = \frac{1}{H_0}\]From question 2 we know that \[H_0 = 67 \frac{km}{MPc \cdot s}\]We need to convert his by getting rid of the distance component and turning seconds into years. \[67 \frac{km}{MPc \cdot s} \thickapprox 7 x 10^{-11} \frac{1}{yr}\]And we know that \[t_0 = \frac{1}{H_0} = \frac{1}{7x10^{-11}} = 1.4x10^{12} \, years = 14 \, billions \, years\]

b) What is the size of the observable universe? What you will calculate is known as the Hubble Length.

The Hubble Length is very easy to find once we have the relative time since the big bang. We know that we may only observe as far as light has traveled. Thus the Hubble Length is simply \[d_{hubble} = 14x10^{11} \cdot c = 14 \, billion \, lightyears = 1.3x10^26 \, meters = 4.3x10^9 \, parsecs\]

Since everything seems to be getting away from us, you might be tempted to imagine we are located at the centre of this expansion. But, as you explored in the opening thought experiment, in actuality, everything is rushing away from everything else, everywhere in the universe, in the same way. So, an alien astronomer observing the motion of galaxies in its locality would arrive at the same conclusions we do.

In cosmology, the scale factor, \(a(t)\), is a dimensionless parameter that characterizes the size of the universe and the amount of space in between grid points in the universe at time t. In the current epoch, t = t0 and \(a(t_0) = 1\). \(a(t)\) is a function of time. It changes over time, and it was smaller in the past (since the universe is expanding). This means that two galaxies in the Hubble Flow separated by distance \(d_0 = d(t_0)\) in the present were \(d(t) = a(t)d_0\) apart at time t. The Hubble Constant is also a function of time, and is defined so as to characterize the fractional rate of change of the scale factor: \[H(t) = \frac{1}{a(t)} \frac{da}{dt}\]and the Hubble Law is locally valid for any t: \[v = H(t)d\]where v is the relative recessional velocity between two points and d the distance that separates them.

a) Assume the rate of expansion, \(\dot{a} = \frac{da}{dt}\), has been constant for all time. How long ago was the Big Bang (i.e. when a(t = 0) 0)? How does this compare with the age of the oldest globular clusters (~12 Gyr)? What you will calculate is known as the Hubble Time.

We want to solve for the time We are given that \(a_0\) is the base at which we characterize the size of the universe from the current epoch and assumes the number 1. We also know that \(H_0\) is a constant for the the current epoch found in question #2 of the worksheet. Using this information we can solve show that \[H_0 = \frac{\dot{a}}{a_0}\]Because we said that a = 1 at the current epoch we can say that \[H_0 = \dot{a} = \frac{da}{dt}\]We then get \[\int_{0}^{t_0} da = \int_{0}^{t_0} H_0 dt\]Which gives us \[a(t_0) = H_0 t_0\]We are looking to solve for \(t_0\) and once we rearrange we get \[t_0 = \frac{1}{H_0}\]From question 2 we know that \[H_0 = 67 \frac{km}{MPc \cdot s}\]We need to convert his by getting rid of the distance component and turning seconds into years. \[67 \frac{km}{MPc \cdot s} \thickapprox 7 x 10^{-11} \frac{1}{yr}\]And we know that \[t_0 = \frac{1}{H_0} = \frac{1}{7x10^{-11}} = 1.4x10^{12} \, years = 14 \, billions \, years\]

b) What is the size of the observable universe? What you will calculate is known as the Hubble Length.

The Hubble Length is very easy to find once we have the relative time since the big bang. We know that we may only observe as far as light has traveled. Thus the Hubble Length is simply \[d_{hubble} = 14x10^{11} \cdot c = 14 \, billion \, lightyears = 1.3x10^26 \, meters = 4.3x10^9 \, parsecs\]

Blog #26, Worksheet #8.1, Problem #1, Hubble Flow Thought Experiment

1. Before we dive into the Hubble Flow, let’s do a thought experiment. Pretend that there is an

infinitely long series of balls sitting in a row. Imagine that during a time interval \(\Delta t\) the space

between each ball increases by \(\Delta x\)

(a) Look at the shaded ball, Ball C, in the figure above. Imagine that Ball C is sitting still (so we are in the reference frame of Ball C). What is the distance to Ball D after time ∆t? What about Ball B?

Let's call the original distance between Ball C and Ball D, x. Then we know that after a time \(\Delta t\) the ball travels a distance \(\Delta X\). Thus our total distance after a time \(\Delta t\) is \[d = x + \Delta x\]Because every ball is evenly spaced, we can assume that Ball B travels the same distance as Ball D.

(b) What are the distances from Ball C to Ball A and Ball E?

Both Ball A and Ball E begin at a distance \(2x\) away from Ball C and over the course of time \(\Delta t\), the each ball has traveled a distance \(\Delta x\) away from the ball next to them which has also traveled a distance \(\Delta x\) from Ball C. Giving the total distance of Ball A/E away from Ball C as \[d = 2x + 2 \Delta x\]

(c) Write a general expression for the distance to a ball N balls away from Ball C after time ∆t. Interpret your finding.

Seeing the pattern from part a) and b) we can easily generalize our equation for a ball N balls away as \[d = Nx + N \delta x\]

(d) Write the velocity of a ball N balls away from Ball C during ∆t. Interpret your finding.

Velocity is simply distance over time and we know that the distance a Ball N balls away from travels is \[d = N \Delta x \]Thus our velocity comes out to be \[v = \frac{N \Delta x}{\Delta t} = Nv\]

(a) Look at the shaded ball, Ball C, in the figure above. Imagine that Ball C is sitting still (so we are in the reference frame of Ball C). What is the distance to Ball D after time ∆t? What about Ball B?

Let's call the original distance between Ball C and Ball D, x. Then we know that after a time \(\Delta t\) the ball travels a distance \(\Delta X\). Thus our total distance after a time \(\Delta t\) is \[d = x + \Delta x\]Because every ball is evenly spaced, we can assume that Ball B travels the same distance as Ball D.

(b) What are the distances from Ball C to Ball A and Ball E?

Both Ball A and Ball E begin at a distance \(2x\) away from Ball C and over the course of time \(\Delta t\), the each ball has traveled a distance \(\Delta x\) away from the ball next to them which has also traveled a distance \(\Delta x\) from Ball C. Giving the total distance of Ball A/E away from Ball C as \[d = 2x + 2 \Delta x\]

(c) Write a general expression for the distance to a ball N balls away from Ball C after time ∆t. Interpret your finding.

Seeing the pattern from part a) and b) we can easily generalize our equation for a ball N balls away as \[d = Nx + N \delta x\]

(d) Write the velocity of a ball N balls away from Ball C during ∆t. Interpret your finding.

Velocity is simply distance over time and we know that the distance a Ball N balls away from travels is \[d = N \Delta x \]Thus our velocity comes out to be \[v = \frac{N \Delta x}{\Delta t} = Nv\]

Blog #25, Worksheet #7.2, Problem #5, Red Shifts of Different Spectrums

5. You may also have noticed some weak “dips” (or absorption features) in the spectrum:

(a) Suggest some plausible origins for these features. By way of inspiration, you may want to consider what might occur if the bright light from this quasar’s accretion disk encounters some gaseous material on its way to Earth. That gaseous material will definitely contain hydrogen, and those hydrogen atoms will probably have electrons occupying the lowest allowed energy state.

As somewhat explained in the question, on it's way to Earth, the emitted light from the quasar may hit very thick patches of gasses, notably hydrogen. As we explored earlier in the worksheet, these hydrogen molecules absorb some of the emitted energy and use it to move through energy levels. They then output the LyA wavelength as output and we use this wavelength change to measure the speed at which the the quasar, or other object, is moving away from us at. The dips in the light spectrum curve symbolize the patches of hydrogen gas that the light encounters at certain wavelengths. Instead of the steady dispersion of different wavelengths on the spectrum, certain ones are absorbed by the clouds of hydrogen and then account for a much smaller flux being received on Earth.

(b) A spectrum of a different quasar is shown below. Assuming the strongest emission line you see here is due to Lyα, what is the approximate redshift of this object?

We use the equation for red shift that we saw earlier \[z = \frac{\lambda_{observed} - \lambda_{emitted}}{\lambda_{emitted}}\]We assume that the peak in the light spectrum offers a good estimate for the observed wavelength. We also know that the emitted wavelength in a redshift is the LyA shift where \(\lambda = 1215.67 \, angstroms\). We find that the peak is around \(\lambda = 5650 \, angstroms\). Plugging into our equation and solving for z, we get a redshift of \[z = 3.65\]This shift is much more significant than the first spectrum we looked at. This larger redshift means that the quasar is moving much faster and must be significantly further away from Earth.

(c) What is the most noticeable difference between this spectrum and the spectrum of 3C 273? What conclusion might we draw regarding the incidence of gas in the early Universe as compared to the nearby Universe?

It is clear that on this spectrum, compared to the first, that there are far more peaks and valleys. Far more emission jumps and absorption lines. As we discovered in part a) these are created by light hitting patches of hydrogen along the journey from the quasar to Earth. Given that we found the second quasar to be much further than the original quasar, and the fact that there are far more absorption lines in the second spectrum, we can assume there is much more gaseous material in the earlier universe than there is in the nearby, developed universe. The larger the redshift and older the quasar is, the more absorption lines it should have.

Blog #24, Worksheet #7.2, Question #2, Eddington Luminosity

2. There is actually a hard upper limit to the luminosity of this system – and to the luminosity of any accreting compact object. Consider that the photons being emitted in this scenario will interact with the surrounding material (which has yet to accrete onto the black hole). These photons will undergo Thomson scattering off of electrons in this material. In detail, the electric field of the incident lightwave (i.e., the photon) will accelerate an electron, causing it to then re-emit radiation. The photons are therefore able to transfer some of their momentum to the infalling gas. The energy flux of these photons at a distance r from the black hole is \[F = \frac{L}{4 \pi r^2}\]

Then, recall that the momentum of a photon of energy E is simply p = E/c. Therefore, the momentum flux at r from the black hole is \(\frac{L}{4πcr^2}\).

Finally, the rate of momentum transfer to the surrounding electrons (or the force due

to photons \((f_{rad})\) is modulated by the Thomson cross section, \(\sigma_t = 6.6524 \, x \, 10^{-25} \, cm^2\) (i.e., the effective area of an electron interacting with a photon): \[f_{rad} = \sigma_t \frac{L}{4 \pi c r^2}\]

(a) When this force from radiation pressure exceeds the force of gravity, accretion is

halted and all the gas is blown away. For a black hole mass \(M_{BH}\), derive the maximum

possible luminosity due to accretion. This is called the Eddington Luminosity.

We begin with the fact that we know the momentum flux and the force of the radiation \[Flux_{\rho} = \frac{L}{4 \pi cr^2} \qquad and \qquad f_{rad} = \sigma_t \frac{L}{4 \pi c r^2}\]Then to solve for the maximum luminosity, we set the force of the radiation equal to the force of gravity from the black hole on the protons. When the force of radiation is larger, all accretion is halted and the gas leaves the disk. \[f_{rad} = \sigma_t \frac{L}{4 \pi c r^2} = \frac{G M_{BH} M_{proton}}{r^2}\]And finally we solve for our Eddington Luminosity \[L_{max} = \frac{4 \pi c G M_{BH} M_{proton}}{\sigma_t}\]

Bonus: Express the Eddington Luminosity as a number of Solar luminosities, L , and the black hole mass in solar masses \((\frac{M_{BH}}{M_{\odot}})\), such that \[L_{Edd} = X(\frac{M_{BH}}{M_{\odot}}) \cdot L_{\odot} \]

We need our Eddison Luminosity from part a) to equal the equation on the right side. Thus, we have \[\frac{4 \pi c G M_{BH} M_{proton}}{\sigma_t} = X(\frac{M_{BH}}{M_{\odot}}) \cdot L_{\odot} \]Then we simply simplify and solve for X to give us \[X = \frac{4 \pi c G M_{proton}}{\sigma_t} \cdot \frac {M_{\odot}}{L_{\odot}} \]

(b) If the SMBH in Andromeda were accreting at 20% of its Eddington luminosity, how

bright would it be?

We know the Eddington Luminosity can be found with the equation \[L_{Edd} = \frac {4 \pi c G M_{BH} M{proton}}{\sigma_t}\]From Wikipedia we estimate that the mass of the SMBH at the center of Andromeda is about \(10^8 \, M_{\odot} \). We also know that the mass of a proton is \(1.67 x 10^{-27} \, kg\).

Plugging in and solving for the Eddison Luminosity, we get: \[L_{Edd} = 1.257 \, x \, 10^{39} \frac{J}{s}\]However, we are given that the SMBH is operating at 20% of its Eddison Luminosity, giving us \[L = 2.515 \, x \, 10^{38} \frac{J}{s}\]

Sources Used

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supermassive_black_hole

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Blog #23, Free Form Post, Asteroid Mining

There is quite a bit of intersection when it comes to astronomy and economics. Unfortunately, usually that pertains to how much money should be cut from national budgets funding space programs. Luckily all of the research and discovery over the past few decades has led to a new a branch of space exploration that may actually bring in huge profits to space companies. Asteroid mining is a hot new branch of space exploration focused on extracting rare metals and gasses from asteroids or other near-earth space objects and bringing using the goods to turn a substantial profit.

The two main companies focused on asteroid mining right now are Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries. Each is a venture backed startup that looks to put its own mining devices onto asteroids and mine for precious materials. The first, and most immediately exciting, prospect of asteroid mining is the money. Researchers believe that in a single asteroid, 1km in diameter, could contain enough nickel ore to supply the Earth for the next 70 million years.

Beyond nickel, iron, and gold, asteroid miners are most excited about the vast abundance of platinum in space. Platinum is relatively rare on the Earth but makes up a significant portion of many asteroids. In a recent article from Space.com, it was predicted that asteroid 2011 UW158 missed the Earth by about 1.5 million miles, roughly the distance from the Earth to the Moon. Although not a very close miss, the asteroid got potential miners very excited as it was predicted to hold up to $20 trillion dollars worth of platinum at the current market price. Trillion. With a t. These kinds of prices are what gets Planetary Resources' engineers to work every morning and what keeps thousands of investors interested in the somewhat crazy sounding business plan.

Still there are skeptics that criticize the idea of mining as a significant waste of money. They argue that the cost of a trip in addition the experimentation and all of the materials required to actually land on an asteroid and extract anything useful far outweigh the current market for the materials they look to bring back to Earth. Economists also argue that such an influx in precious metals may saturate the market, deeming the metals brought back essentially useless, and certainly not worth $20 trillion.

Regardless of who is correct in the economic debate, the prospect of consistently bringing material back to Earth for commercial use is certainly an entertaining prospect. It is exciting to live in a time where the technology is available and ever progressing, allowing humans to do things that were previously considered a dream or a goal far out of reach.

Sources:

http://www.planetaryresources.com/company/overview/

http://www.space.com/30074-trillion-dollar-asteroid-2011-uw158-earth-flyby.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLouRKHknOU

http://www.wired.com/images_blogs/wiredscience/2012/04/SEP_Airlock_Concept.jpg

https://62e528761d0685343e1c-f3d1b99a743ffa4142d9d7f1978d9686.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/files/10153/area14mp/35vqmr6c-1335830904.jpg

The two main companies focused on asteroid mining right now are Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries. Each is a venture backed startup that looks to put its own mining devices onto asteroids and mine for precious materials. The first, and most immediately exciting, prospect of asteroid mining is the money. Researchers believe that in a single asteroid, 1km in diameter, could contain enough nickel ore to supply the Earth for the next 70 million years.

Beyond nickel, iron, and gold, asteroid miners are most excited about the vast abundance of platinum in space. Platinum is relatively rare on the Earth but makes up a significant portion of many asteroids. In a recent article from Space.com, it was predicted that asteroid 2011 UW158 missed the Earth by about 1.5 million miles, roughly the distance from the Earth to the Moon. Although not a very close miss, the asteroid got potential miners very excited as it was predicted to hold up to $20 trillion dollars worth of platinum at the current market price. Trillion. With a t. These kinds of prices are what gets Planetary Resources' engineers to work every morning and what keeps thousands of investors interested in the somewhat crazy sounding business plan.

Still there are skeptics that criticize the idea of mining as a significant waste of money. They argue that the cost of a trip in addition the experimentation and all of the materials required to actually land on an asteroid and extract anything useful far outweigh the current market for the materials they look to bring back to Earth. Economists also argue that such an influx in precious metals may saturate the market, deeming the metals brought back essentially useless, and certainly not worth $20 trillion.

Regardless of who is correct in the economic debate, the prospect of consistently bringing material back to Earth for commercial use is certainly an entertaining prospect. It is exciting to live in a time where the technology is available and ever progressing, allowing humans to do things that were previously considered a dream or a goal far out of reach.

Sources:

http://www.planetaryresources.com/company/overview/

http://www.space.com/30074-trillion-dollar-asteroid-2011-uw158-earth-flyby.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLouRKHknOU

http://www.wired.com/images_blogs/wiredscience/2012/04/SEP_Airlock_Concept.jpg

https://62e528761d0685343e1c-f3d1b99a743ffa4142d9d7f1978d9686.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/files/10153/area14mp/35vqmr6c-1335830904.jpg

Blog #22, Worksheet #7.1, Problem #2, Sound Speed of White Dwarf

2. Use the previous result to derive the sound speed, \(c_s\), within the white dwarf, where \(c_s\) can be related to pressure, \(P\), and mass density, \(\rho\), using dimensional analysis (make the units work).

We begin with our expression from question 1 for Pressure \[P = \frac{GM^2}{4 \pi R^4}\]We then look at the units for this expression \[P = \frac{[F]}{m^2} = \frac{kg \cdot m}{m^2 \cdot s^2} = \frac{kg}{m \cdot s^2}\]We want to solve for \(c_s\) which has units \(\frac{m}{s}\), so we must find some exponent for both density and pressure that gives us the \(\frac{m}{s}\) relationship we need. Density, \(\rho\) has the units \[\rho = \frac{kg}{m^3}\]So we end up with the relationship \[(\frac{kg}{m \cdot s^2})^{\alpha} \cdot (\frac{kg}{m^3})^{\beta} = \frac{m}{s}\]We then need to figure out what exponents for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) lead us the the correct units for velocity. After a quick inspection we can clearly see the the density should be in the denominator of our equation and after canceling, we need to take the square root of both equations to get the proper units for velocity. Thus \[\alpha = \frac{1}{2} \, and \, \beta = -\frac{1}{2}\]Thus our final answer gives us \[c_s \propto (\frac{P}{\rho})^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

We begin with our expression from question 1 for Pressure \[P = \frac{GM^2}{4 \pi R^4}\]We then look at the units for this expression \[P = \frac{[F]}{m^2} = \frac{kg \cdot m}{m^2 \cdot s^2} = \frac{kg}{m \cdot s^2}\]We want to solve for \(c_s\) which has units \(\frac{m}{s}\), so we must find some exponent for both density and pressure that gives us the \(\frac{m}{s}\) relationship we need. Density, \(\rho\) has the units \[\rho = \frac{kg}{m^3}\]So we end up with the relationship \[(\frac{kg}{m \cdot s^2})^{\alpha} \cdot (\frac{kg}{m^3})^{\beta} = \frac{m}{s}\]We then need to figure out what exponents for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) lead us the the correct units for velocity. After a quick inspection we can clearly see the the density should be in the denominator of our equation and after canceling, we need to take the square root of both equations to get the proper units for velocity. Thus \[\alpha = \frac{1}{2} \, and \, \beta = -\frac{1}{2}\]Thus our final answer gives us \[c_s \propto (\frac{P}{\rho})^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

Blog #21, Worksheet #7.1, #1, Electron Degeneracy Pressure

1. Given this mass, M and radius, R, derive an algebraic expression for for the internal pressure of a white dwarf with these properties. Start with the Virial theorem, recall that the internal kinetic energy per particle is \(\frac{3}{2}kT\), where \(k = 1.4 x 10^{-16} \, erg \, K^{-1} \) is the Boltzmann constant. You can also assume the interior of the white dwarf is an ideal gas, and its mass is uniformly distributed.

We begin by using the fact that the internal structure of the white dwarf acts as an ideal gas. We can use the standard formula for pressure \[P = \frac{NkT}{V}\] Where N is the number of molecules, k is the Boltzmann constant \((k = 1.4 x 10^{-16} \, erg \, K^{-1})\), T is temperature, and V is the volume. In our case, \[V = \frac{4}{3} \pi R^3\]Combining these equations we get an equation for P. \[P = \frac{3NkT}{4 \pi R^3} \]Next we use the Virial theorem to try and get rid of the N in our Pressure equation. We know that \[K = - \frac{1}{2} U = \frac {3}{2} NkT\]Where \[U = \frac{GM^2}{R}\]Setting the equations equal to one another and simplifying to solve for N, we get \[N = \frac{GM^2}{3RkT}\]We then substitute this variable into our equation for P and get a final answer of \[P = \frac{3kT}{4 \pi R^3} \cdot \frac{GM^2}{3RkT} = \frac{GM^2}{4 \pi R^4}\]

We begin by using the fact that the internal structure of the white dwarf acts as an ideal gas. We can use the standard formula for pressure \[P = \frac{NkT}{V}\] Where N is the number of molecules, k is the Boltzmann constant \((k = 1.4 x 10^{-16} \, erg \, K^{-1})\), T is temperature, and V is the volume. In our case, \[V = \frac{4}{3} \pi R^3\]Combining these equations we get an equation for P. \[P = \frac{3NkT}{4 \pi R^3} \]Next we use the Virial theorem to try and get rid of the N in our Pressure equation. We know that \[K = - \frac{1}{2} U = \frac {3}{2} NkT\]Where \[U = \frac{GM^2}{R}\]Setting the equations equal to one another and simplifying to solve for N, we get \[N = \frac{GM^2}{3RkT}\]We then substitute this variable into our equation for P and get a final answer of \[P = \frac{3kT}{4 \pi R^3} \cdot \frac{GM^2}{3RkT} = \frac{GM^2}{4 \pi R^4}\]

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Blog #18, Worksheet #6.1, Problem #4, Tully-fisher

4) Over time, from measurements of the photometric and kinematic properties of normal galaxies, it

became apparent that there exist correlations between the amount of motion of objects in the galaxy

and the galaxy’s luminosity. In this problem, we’ll explore one of these relationships.

Spiral galaxies obey the Tully-Fisher Relation: \[L \propto v^4\]where L is total luminosity, and vmax is the maximum observed rotational velocity. This relation

was initially discovered observationally, but it is not hard to derive in a crude way:

(a) Assume that \(v_{max} \thickapprox σ\) (is this a good assumption?). Given what you know about the Virial Theorem, how should \(v_{max} \)relate to the mass and radius of the Galaxy?

We can assume that \(v_{max} \thickapprox σ\) because the mean velocity scatter will of course be lower than the maximum observed velocity. However, because the grouping of stars are roughly similar, the maximum observed velocity will not be much higher than the mean unless there is an anomaly. Thus it will not be too far off to approximate the scatter velocity as the vmax of the system.

We can use knowledge of the Virial Theorem to then relate mass and radius to the vmax using what we found from problem #3. \[M = \frac{\sigma ^2 R}{G}\] Thus \[\sigma = (\frac{GM}{R})^{\frac{1}{2}} \thickapprox v_{max}\]

(b) To proceed from here, you need some handy observational facts. First, all spiral galaxies have a similar disk surface brightnesses \(I = \frac{L}{R^2}\) Freeman’s Law. Second, they also have similar total mass-to-light ratios \(\frac{M}{L}\).

(c) Use some squiggle math (drop the constants and use \(\thickapprox \) instead of =) to find the Tully-Fisher relationship.

We will use general proportionality to find the Tully-Fisher relation. We know from part one that \[v_{max}^2 \propto \frac{M}{R} \] We know from Freeman's law that \[R \propto L^{\frac{1}{2}}\]We also know that \(M \propto L\) from the mass-to-light ratio. Plugging in this info, we get \[v_{max}^2 \propto \frac{L}{L^{\frac{1}{2}}}\]If we square this, we get to the Tully-Fisher relation \[L \propto v^4\]

(d) It turns out the Tully-Fisher Relation is so well-obeyed that it can be used as a standard candle, just like the Cepheids and Supernova Ia you saw in the last worksheet. In the B-band \(λ_{cen} \thickapprox 445 nm \) blue light, this relation is approximately: \[M_B = -10 \, log(\frac{v_{max}}{km/s}) + 3 \]