Below please find a small educational video explaining the general concepts on dark matter and how astrophysicists are able to detect it without seeing it!

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

Blog #38, Extra Credit Video Project, Dark Matter

Below please find a small educational video explaining the general concepts on dark matter and how astrophysicists are able to detect it without seeing it!

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Blog #36, Worksheet #12.1, Problem #1 and 2(d), Dark Matter Halos

1. Linear perturbation theory. In this and the next exercise we study how small fluctuations in the initial condition of the universe evolve with time, using some basic fluid dynamics. In the early universe, the matter/radiation distribution of the universe is very homogeneous and isotropic. At any given time, let us denote the average density of the universe as p(t). Nonetheless, there are some tiny fluctuations and not everywhere exactly the same. So let us define the density at co-moving position r and time t as ρ(x,t) and the relative density contrast.

In this exercise we focus on the linear theory, namely, the density contrast in the problem remains small enough so we only need consider terms linear in δ. We assume that cold dark matter, which behaves like dust (that is, it is pressureless) dominates the content of the universe at the early epoch. The absence of pressure simplifies the fluid dynamics equations used to characterize the problem.

a) In the linear theory, it turns out that the fluid equations simplify such that the density contrast δ satisfies the following second-order differential equation.

where a(t) is the scale factor of the universe. Notice that remarkably in the linear theory this equation does not contain spatial derivatives. Show that this means that the spatial shape of the density fluctuations is frozen in comoving coordinates, only their amplitude changes. Namely this means that we can factorize

Derive this differential equation.

We begin with the equation \[\ddot{\delta} + \frac{2 \dot{a}}{a} \dot{\delta} = 4 \pi G \bar{\rho} \delta\]We then use the relationship that \[\delta = D \tilde{\delta}\]We then plug in and simplify our equation to get a quadratic with variable D. \[\ddot{D} + \frac{2 \dot{a}}{a} \dot{D} - 4 \pi G \bar{\rho} D = 0 \]

b) Now let us consider a matter dominated flat universe, so that ρ(t) = a^-3ρ(c,0) where ρ(c,0) is the critical density today, 3H^2/8πG as in Worksheet 11.1 (aside: such a universe sometimes is called the Einstein-de Sitter model). Recall that the behaviour of the scale factor of this universe can be written a(t) = (3Ht/2)^2/3 , which you learned in previous worksheets, and solve the differential equation for D(t). Hint: you can use the ansatz D(t) is prop to t^q and plug it into the equation that you derived above; and you will end up with a quadratic equation for q. There are two solutions for q, and the general solution for D is a linear combination of two components: One gives you a growing function in t, denoting it as D(t); another decreasing function in t, denoting it as D(t).

We are then given that \[\bar{\rho} = a^{-3} {\rho}_{c,o}\]Where \[a = (\frac{3 H_0 t}{2})^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad {\rho}_{c,o} = \frac{3 H_0}{8 \pi G}\]We combine these to show \[\bar{\rho} = \frac{1}{6 \pi G t^2}\]We are then asked to approximate \(D\) as \(t^q

\). Plugging this into our quadratic, along with \(\bar{\rho}\), \(a\) and \(\dot{a}\) we get \[0 = (q)(q-1)t^{q-2} + \frac{4q}{3}t^{q-2} - \frac{2}{3}t^{q-2}\]We divide by \(t^{q-2}\) and simplify to get \[q^2 + \frac{1}{3}q - \frac{2}{3} = 0\]Then we solve for q to get \[q = \frac{2}{3}, -1\] Which is the desired positive side and negative side solution that we expected. To solve for a final D, we put our two answers into a linear combination to give us \[D = t^{-1} + t^{\frac{2}{3}}\]where \[D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}} \qquad and \qquad D_- = t^{-1}\]

c) Explain why the D component is generically the dominant one in structure formation, and show that in the Einstein-de Sitter model, D(t) prop to a(t).

We can see of the bat that our \(D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) is proportion to \(a(t) = (\frac{3 H_0 t}{2})^{\frac{2}{3}}\) and the two will increase proportionally. We can also see that \(D_+ = t^{\frac{2}{3}}\) will increase much faster than \(D_- = \frac{1}{t}\) and thus will dominate the overall D formula.

2d) Plot r as a function of t for all three cases (i.e. use y-axis for r and x-axis for t), and show that in the closed case, the particle turns around and collapse; in the open case, the particle keeps expanding with some asymptotically positive velocity; and in the flat case, the particle reaches an infinite radius but with a velocity that approaches zero.

In the first plot we can see the closed case, where the particle turns and collapses back to an incredibly small radius.

Eventually this graph will hit an asymptotically high velocity in which the particle is increasing radius at nearly an infinite rate. This is the case when the universe is modeled in an open system.

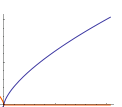

Finally for the flat case we can see that the radius is ever expanding but at a decreasing rate that will eventually flatten to a zero velocity.

#37, Free Form Post, Illustris Write Up

Illustris

The Illustris simulation is a massive computer program simulating the entire universe in its galaxies, black holes, gas dispersion, and even dark matter. The entire simulation has been compiled onto www.illustris-project.org and includes various images and videos that run through the hypothetical formation of the universe through various mediums.

We began our exploration by examining a 15 Mpc/h deep slice of the simulation. Shown below is the filter displaying the density of dark matter in the simulated universe. The lighter the shade of purple, the more densely packed the dark matter is.

We then selected a small portion of the simulation and ran a "halo query" to find the characteristics of a group of galaxies and their surrounding dark matter. The query returns the galaxy ID, position, stellar mass, halo mass, color, and magnitude for around 20 different galaxies in the selected 400 kpc/h portion.

We then created a histogram based on the halo mass and stellar mass of the selected galaxies.

From this plot we can see that while the stellar masses are relatively well distributed, the halo masses far favor the low mass halos. We can also determine the average amount of the halo mass that is made up of the stellar mass. Taking each percentage of (stellar mass/halo mass) and taking the average we can see that on average about 80% of the halo mass is made up of the stellar mass.

Exploring structure and Reionization

We then used various filters on the simulation to explore the differences between the stellar, gas, and dark matter densities of the structure. We looked at the gas and dark matter densities on large and small scales to find that while very similar on large and small scales, the dark matter is far more structured a large scale and the gas has much more form at very small scales (galactic scale). Still overall the gas has more form but less structure than the dark matter density over all. The stellar density is far less than both the gas and dark matter, but is incredibly well formed.

From the simulation we can see that the dark matter is far more structured than the universal gas density. This is because dark matter does not hold pressure and remains at very low temperature compared to its gas counterpart that gets very hot. The heat in the gas causes repelling forces that counter the gravitational forces that are trying to create the form of the universe. The dark matter remains cold and is almost solely worked on by the gravitational forces which can nicely form the dark matter into the filament like structure.

From the simulation we can also see some characteristics about the gas and dark matter distributions. For example, the densest parts of the gas are found towards the nuclei of medium to large galaxies as compared to the disk which moves outward at a less dense gradient. We can also see that most of the large galaxies accumulate in the clusters at filament centers rather than in open space. This is likely because the large masses of these galaxies create stronger gravitational pulls and bring together other large galaxies into major galactic clusters.

We were then asked to explore a video of the formation of the simulation. The video can be seen below:

The video shows the side by side development of the dark matter and gas of the simulated universe. We learned in previous worksheets that the developing gas was mostly hydrogen that absorbed much of the light before it was ionized and broken apart. The right simulation shows the slow development of gas over time as hydrogen absorbed most of the energy but did not ionize for a long period of time.

We can immediately see that dark matter dominated the development of the universe, forming much more complex structures before the gas even begins to form. You can see the filament structures of the dark matter forming far before the gas follows a similar formation pattern.

At a redshift of around 7.5 (or 0.7 billion years after the big bang) we begin to see the formation of the first ionized gasses. This is the end of the dark era mentioned above and brought forth the "epoch of reionization, as hydrogen molecules began to spread and make more complex structures.

During the redshift 2->0.5 we see the fastest development of galaxies and stellar mass. moving quickly from around 12->60 billion solar masses in the universe. During this time we see larger gas and dark matter structures breaking down into smaller ones, pulling nearby elements toward them to form larger structures and then continuously breaking down again. This hierarchal structure likely stems from the a central explosion (the big bang) starting the chain of events that created the rest of the structure for the universe over time. The gravity of the universe pulls objects closer together until their forces overwhelm and they must break apart to form new structures.

As mentioned before over a long time, the gravitational forces overcome their weaker intermolecular forces and pull the gas and dark matter of the structure into a filament form. However there is still interaction between the clusters and thus the clusters cannot form perfect spheres as we saw in the worksheet with halo collapse. There are too many forces present for the clusters to remain perfectly spherical and instead interact in such a way that they form longer, spindle like structures throughout the universe.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)