What is TRAPPIST?

A lot of excitement was generated on February 22, 2017 when NASA released a press statement announcing the founding of 7 exoplanets orbiting a star 12 parsecs from Earth. Using transit photometry, as discussed in earlier blog posts, the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) was able to record the presence of 7 exoplanets around a single star, 5 of which appear to be in or around the habitable zone while 3 have roughly Earth-sized radii.

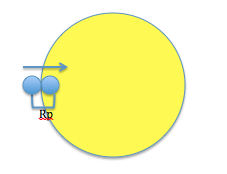

TRAPPIST is actually a system of two 60-cm reflective, optical telescopes. The first, TRAPPIST-South is located in the Chilean mountains at La Silla Observatory while TRAPPIST-North is located in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Despite their locations, both telescopes are controlled out of Liege, Belgium and operate under fully autonomous, robotic systems. The team of telescopes creates photometry data by observing when planets transit across their host stars, causing an observed drop in incoming flux. The plot below shows the process for determining the transit of a planet which helps determine its period, radius, and location around a star.

When it came to the 7 planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, the photometry data was truling startling as the 7 planets all created well defined transit drops. Below is the aligned data for all 7 planets as well as the brightness plots and a schematic of the orbits for the star system.

The bottom left image is the aligned 7 photometry plots with clear ingress and egress dips and corresponding transit depths. These images in conjunction with the TRAPPIST telescopes were imaged by the Spitzer Space Telescope.